Tenants in Common vs Joint Tenants: Essential Differences for Ontario Property Owners

When you’re buying property with someone else in Ontario, the choice between being tenants in common vs joint tenants really boils down to one crucial question: What happens to your share of the property when you die?

It might seem like a small detail on a legal document, but this decision has massive implications. With joint tenancy, your interest automatically passes to the surviving co-owner, completely bypassing your will. This is called the “right of survivorship.” On the other hand, tenants in common treats your share as your own distinct asset, allowing it to pass to your chosen heirs through your estate.

Understanding the Two Paths to Co-Ownership

Deciding how to hold title is one of the most critical choices you’ll make in any real estate deal here in Ontario. It directly shapes your estate planning, inheritance rights, and what each owner can do with their portion of the property. The two main setups, joint tenancy and tenants in common, are built for very different goals and life situations.

Joint Tenancy vs Tenants in Common: A Quick Comparison

Before we get into the finer details, it helps to see the core differences side-by-side. This choice dictates everything from who inherits the property to whether your ownership stakes have to be equal.

Here’s a snapshot to help you quickly grasp the key distinctions.

| Key Feature | Joint Tenants | Tenants in Common |

|---|---|---|

| Right of Survivorship | Yes, the property automatically passes to the surviving owner(s). | No, your share goes to your estate and is handled by your will. |

| Ownership Shares | Must always be equal among all owners. | Can be unequal (e.g., 60/40, 70/30). |

| Transfer of Interest | Requires a legal process to “sever” the joint tenancy first. | Each owner can sell, mortgage, or will their share independently. |

| Probate Process | The property transfer avoids the probate process. | Your share of the property is subject to probate fees and process. |

| Common Use Case | Married or common-law couples buying their family home. | Unmarried partners, investors, friends, or family with different financial contributions. |

This table lays out the fundamental mechanics, but the real-world impact comes down to your specific circumstances and what you want for the future.

The Default Rule in Ontario

Here’s something many people don’t realize: in Ontario, if the property deed doesn’t explicitly state that the owners are “joint tenants,” the law automatically assumes it’s a tenancy in common. This default rule really highlights how important it is to be precise with the legal wording on your documents to make sure your true intentions are locked in.

The most crucial takeaway is this: joint tenancy is built for simplicity and automatic inheritance between co-owners. Tenants in common is all about flexibility and individual control over your estate.

Getting these concepts straight from the start is essential. When you’re looking at more complex ownership arrangements, especially for investment properties, it can also be helpful to understand different types of real estate syndication structures, which offer other ways to define how a property is owned and managed.

Ultimately, making an informed choice now can save your loved ones from some serious legal and financial headaches down the road. To make sure your property ownership lines up with your overall financial plan, you can learn more about how it all connects with wills and estate law.

How Joint Tenancy Simplifies Estate Transfers

In Ontario, when people talk about co-owning property, joint tenancy often comes up first. Its main appeal lies in one powerful legal concept: the right of survivorship. This single feature is the bedrock of joint tenancy and dramatically changes what happens to the property when one of the owners dies.

Think of it this way: with tenants in common, each owner’s share is a distinct piece of their personal assets. When they pass away, that share gets wrapped up in their estate. Joint tenancy, however, creates a seamless transition. The moment one joint tenant dies, their ownership interest instantly and automatically transfers to the surviving owner(s).

This all happens outside of the deceased’s will. More importantly, it completely bypasses the often slow and expensive probate process.

The Power of the Right of Survivorship

The right of survivorship is exactly why joint tenancy is the go-to choice for many, especially married couples buying their family home in Ontario. It’s designed for simplicity and certainty. The property stays with the surviving co-owner without getting tied up in legal red tape.

Because the property doesn’t become part of the deceased’s estate, it isn’t subject to Ontario’s Estate Administration Tax (what most people call probate fees). This can mean real, significant savings for the surviving family. Properly understanding how co-ownership works is vital, particularly for anyone navigating the complexities of properties in probate for sale.

Key Takeaway: In a joint tenancy, the right of survivorship is absolute. It overrides whatever is written in a will. Even if a will leaves the property to a child, the law of joint tenancy ensures the surviving co-owner inherits the entire property.

For anyone aiming to streamline their estate plan, this is a huge benefit. If you want to see just how much is involved in settling an estate, our guide on how to probate a will in Ontario breaks down the typical steps.

The Four Unities: A Strict Requirement

For a joint tenancy to be legally sound in Ontario, it has to meet four very strict conditions, known in the legal world as the “four unities.” These four pillars work together to create a single, unified ownership interest shared equally by all. If even one of these conditions is broken—or “severed”—the joint tenancy dissolves and automatically becomes a tenancy in common.

Here are the four unities:

- Unity of Time: Every joint tenant must have acquired their interest in the property at the very same time.

- Unity of Title: All owners must get their interest from the same legal document, like one deed or will.

- Unity of Interest: All joint tenants must hold the same type and size of ownership interest. Their shares have to be perfectly equal.

- Unity of Possession: Each joint tenant has the right to possess and use the entire property, not just a specific portion of it.

Why This Structure Is Not for Everyone

While the simplicity is tempting, the rigidity of joint tenancy can be a major problem. The rule of equal shares means it’s not a good fit for co-owners who put in different amounts of money.

Furthermore, the automatic right of survivorship means you give up the right to decide who inherits your share. This is a critical downside for blended families or anyone who needs to ensure children from a previous relationship are provided for in their will.

The inflexibility is a core issue when deciding between tenants in common vs joint tenants. The latter offers far more control and is often the better choice for more complex family or investment situations.

Why Tenants in Common Offers More Flexibility

While joint tenancy is straightforward, it’s also rigid. Tenants in common, on the other hand, is built for flexibility, making it a far better fit for the complex ownership arrangements we see so often today. It’s the go-to choice in Ontario for co-buyers whose financial situations or estate plans don’t neatly fit into joint tenancy’s strict box.

The real difference comes down to the ownership shares. Unlike the all-or-nothing, equal-shares approach of joint tenancy, tenants in common allows for unequal ownership stakes. This one feature is a game-changer for many buying scenarios across the GTA and the rest of the province.

Unequal Ownership Shares Reflect Reality

Let’s be honest: not everyone brings the same amount of money to the table when buying property. Tenants in common respects this reality, letting you split ownership in a way that truly reflects what each person put in.

For example, imagine one partner puts down 70% of the down payment and handles the bulk of the mortgage payments, while the other contributes 30%. With tenants in common, you can register the title to reflect that exact 70/30 split. This clarity and fairness from day one is incredibly important for:

- Unmarried or Common-Law Partners: Each person’s investment is legally defined and protected based on their actual contribution.

- Real Estate Investors: A group can pool their funds, with ownership percentages directly matching their capital investment.

- Family Members Buying Together: A parent helping a child purchase a home can have their financial contribution recorded as a specific ownership share.

This ability to customize ownership provides a level of transparency and equity that joint tenancy just can’t match.

You Decide Who Inherits Your Share

Here’s the most critical difference: tenants in common has no right of survivorship. This single detail puts you—not an automatic legal rule—in complete control of what happens to your share of the property when you die.

When a tenant in common passes away, their share doesn’t automatically go to the other co-owners. Instead, it becomes a part of their estate, just like any other asset. From there, it’s distributed according to the instructions in their will, following Ontario’s estate administration process.

This is absolutely essential for anyone in a blended family, a second marriage, or for those who want to leave their assets to specific heirs, like children from a previous relationship. It ensures your property goes to the people you choose, not just to whoever else is on title.

This structure is a powerful estate planning tool. If you’re putting together a comprehensive plan, our estate planning checklist for Canada is a great resource for seeing how all the pieces fit together.

Individual Control and Financial Autonomy

The flexibility of tenants in common doesn’t stop at inheritance. Each co-owner’s share is treated as their own distinct asset, giving them a level of financial independence that’s impossible with joint tenancy.

In theory, one owner could sell or mortgage their individual share without getting consent from the others (though practically speaking, finding a buyer or a lender for a partial interest in a property is very difficult). This separation also matters when it comes to creditors. If one co-owner runs into financial difficulty, creditors can generally only place a lien against that person’s specific share, which helps shield the other owners’ interests.

This level of control is precisely why tenancy in common is so popular among common-law partners, couples in second marriages, and families co-owning property in Canada. It provides the essential estate planning control needed to make sure your property assets end up exactly where you intend them to go.

Applying Ownership Models to Real-World Scenarios

The legal theory behind joint tenancy and tenants in common is one thing, but figuring out how it applies to your life is what really matters. The right choice depends entirely on your relationships, who’s putting in what financially, and what you want to happen down the road. Let’s walk through some common situations people in Ontario find themselves in and see which structure makes the most sense.

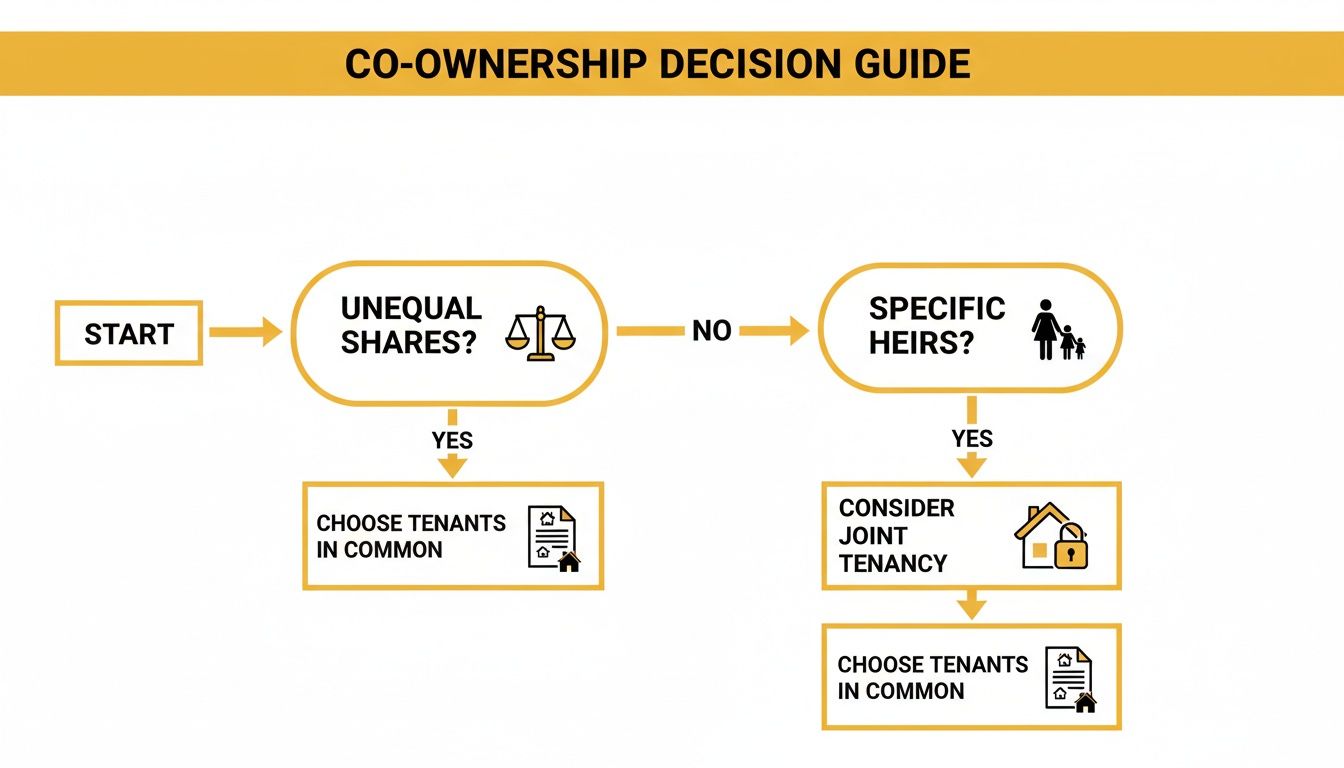

To get started, this flowchart helps visualize the key questions that point most people toward a tenants in common agreement.

As you can see, the moment unequal shares or a desire to leave your portion to specific heirs enters the picture, tenants in common usually becomes the go-to solution.

Scenario 1: Married Couple Buys a Home in the GTA

A married couple is buying their first home together in Burlington. They’ve split the down payment equally and will be sharing all mortgage and household costs. Their main priority is simplicity and making sure the surviving spouse automatically gets the house without any legal headaches.

- Recommended Model: Joint Tenancy is the hands-down winner here.

- Why It Works: The automatic right of survivorship is perfectly aligned with their goals. If one spouse passes away, the other becomes the sole owner of the property instantly. This completely bypasses the will and the often lengthy probate process, offering incredible peace of mind and financial security during a very tough time.

Scenario 2: Common-Law Partners with Blended Families

A common-law couple in Mississauga is purchasing a property. They both have children from previous relationships and have contributed different amounts to the down payment—one partner put down 65%, and the other contributed 35%. Each wants their share of the property to go to their own kids when they die.

- Recommended Model: Tenants in Common isn’t just an option; it’s essential.

- Why It Works: This structure allows them to register their ownership shares on title as a 65/35 split, which mirrors their actual financial contributions. More importantly, it gets rid of the right of survivorship. This means each partner can specify in their will that their share goes to their children. Choosing joint tenancy would be a critical mistake, as it would automatically transfer the entire property to the surviving partner, effectively disinheriting the children of the deceased. This is a crucial distinction, especially for those wondering what is common law marriage in Canada and its impact on property rights.

Key Insight: For blended families, tenants in common is the cornerstone of fair and deliberate estate planning. It’s the only way to ensure children from previous relationships are protected.

Scenario 3: Siblings Inheriting a Muskoka Cottage

Three siblings have just inherited their family cottage in Muskoka. They all love it and want to keep it in the family for years to come, but they also recognize that one of them might need to sell their share one day. They need an ownership model that defines a clear inheritance path for each of their families.

- Recommended Model: Tenants in Common provides the exact flexibility they need.

- Why It Works: Holding the title this way gives each sibling a distinct one-third share. It’s their asset to manage. This means they can will their portion to their own children, keeping the cottage in their direct family line. It also creates a legal framework for one sibling to sell their share—either to the other siblings or an outside party—if their life changes, without having to force a sale of the entire property.

Scenario 4: Friends Co-Investing in a Toronto Rental Property

Two friends are pooling their money to buy a rental condo in downtown Toronto as an investment. One friend is putting in $100,000, and the other is contributing $50,000. They want a clear, business-like arrangement that protects each person’s investment and provides a straightforward exit strategy.

- Recommended Model: Tenants in Common is the only logical choice for this business venture.

- Why It Works: Joint tenancy wouldn’t work because it demands equal shares, which doesn’t reflect their 2:1 investment ratio. Tenants in common allows them to register their ownership as a two-thirds and one-third split on the title. This setup guarantees that if they sell, the profits are divided proportionally. It also means that if one investor were to pass away, their share becomes part of their estate, protecting their family’s financial interest in the property.

Choosing an Ownership Model for Your Situation

This table breaks down the best approach for these common scenarios, helping you see the logic behind the choice.

| Scenario | Recommended Ownership Model | Primary Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Married or long-term couple, first home | Joint Tenancy | Simplicity and automatic inheritance for the surviving partner. |

| Blended family or common-law partners | Tenants in Common | Protecting children’s inheritance and reflecting unequal contributions. |

| Siblings or family members inheriting property | Tenants in Common | Allowing individual inheritance paths and the flexibility to sell a share. |

| Friends or business partners investing | Tenants in Common | Protecting unequal investments and ensuring a clear business-like structure. |

The decision between tenants in common vs joint tenants has lasting financial and personal consequences. By looking at your own life through the lens of these real-world examples, you can make a more informed choice—one that protects your investment, reflects everyone’s contributions, and secures your long-term estate planning goals.

How to Sever a Joint Tenancy in Ontario

A joint tenancy isn’t necessarily a lifelong commitment. Things change—relationships end, financial situations shift, or you might simply want to rethink your estate plan. When the automatic right of survivorship no longer makes sense for you, Ontario law allows you to legally “sever” the joint tenancy, converting it into a tenancy in common. This is a powerful move that gives you back control over who inherits your portion of the property.

What often surprises people is that this can usually be done unilaterally. That’s right—one joint tenant can sever the arrangement without the consent or even the knowledge of the other co-owners. By taking a specific legal action, you can break one of the “four unities” that hold a joint tenancy together, instantly changing the ownership structure to a tenancy in common.

Actions That Legally Sever a Joint Tenancy

In Ontario, the courts have long recognized several specific actions that will effectively sever a joint tenancy. Each path has its own legal and practical considerations.

Here are the most common ways it’s done:

- Transferring Title to Yourself: This is the most straightforward and frequently used method. You can legally transfer your interest in the property from yourself as a joint tenant to yourself as a tenant in common. Once this new deed is registered on title, it unilaterally severs the joint tenancy.

- Selling Your Share to a Third Party: If you sell your interest to an outside buyer, the joint tenancy is immediately broken for that share. The new owner comes into the title at a different time, so they can’t be a joint tenant with the original owners. Their share automatically becomes a tenancy in common.

- Mortgaging Your Share: This one is a bit more complex, but placing a mortgage on your individual interest in the property can also sever the joint tenancy. The courts see a mortgage as a charge against the title that interferes with the unity of all owners’ interests.

- Mutual Agreement: Of course, the cleanest way to sever is for all co-owners to agree to the change. You can all sign a legal agreement to convert the ownership to a tenancy in common, ensuring everyone is on the same page.

Here’s a critical takeaway: Simply stating in your will that you want your share to go to your child or another heir does not work. The right of survivorship legally overrides whatever your will says. The severance has to be completed while all the joint tenants are still alive.

The Legal Process for Severance in Ontario

Just deciding you want to sever the tenancy isn’t enough. To make it legally binding, you have to follow a formal process. If you miss a step, the severance could be deemed invalid, and the right of survivorship would remain in place—likely the exact opposite of what you intended.

The process generally looks like this:

- Draft a Transfer Deed: A lawyer will need to prepare a new deed. This document formally transfers your interest in the property back to yourself, but with crucial new wording specifying the ownership is now as “tenants in common.”

- Register the Deed: The new deed must be registered at the proper Land Registry Office in Ontario. This registration serves as official public notice that the ownership structure has been changed.

- Provide Notice: While you might not need the other owners’ permission, giving them formal written notice that you’ve severed the tenancy is always the best practice and sometimes a legal necessity. It’s a simple step that can prevent a lot of confusion and potential legal battles down the road.

Because the rules are so precise, getting this right is essential. Changing how you own property has major legal and financial ripple effects, touching everything from your mortgage to your estate. To ensure your intentions are protected and the severance is done correctly, it’s a good idea to discuss your wills and estates plan with an experienced Ontario lawyer.

Your Top Co-Ownership Questions Answered

When you’re buying property with someone else in Ontario, the legal fine print matters. A lot. Diving into the specifics of tenants in common vs joint tenants often sparks a number of questions about how it all plays out in the real world. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones we hear from property owners across the GTA.

What Are The Tax Implications Of Each Ownership Type In Ontario?

Taxes are a huge consideration, and how your ownership is structured can have very different outcomes, especially when comparing a principal residence to an investment property.

For your principal residence, things are usually straightforward. Thanks to the principal residence exemption in Canada, you generally don’t pay capital gains tax when you sell your home. This holds true whether you’re joint tenants or tenants in common.

But with an investment property, the rules diverge significantly:

- Joint Tenancy: Think of this as a “deferral” mechanism for tax. When one owner passes away, their share automatically rolls over to the surviving owner(s) without triggering an immediate capital gain. The tax bill only comes due when the last surviving owner sells the property or passes away themselves.

- Tenants in Common: Here, each share is a distinct asset in the eyes of the Canada Revenue Agency. If you sell your share or pass away, capital gains tax applies to your portion. Upon death, your share is considered “disposed of” at its fair market value, and any resulting capital gain is calculated and paid by your estate via your final tax return.

How Does Co-Ownership Affect Mortgage Liability?

This is a point that trips a lot of people up. When you get a mortgage with co-owners, the bank’s main concern is getting its money back.

No matter how you structure your ownership, lenders will almost always require all co-owners to be “jointly and severally liable” for the entire mortgage. In plain English, this means the bank can come after any one of you for the full amount owed. They don’t care about your 50/50 or 70/30 split; to them, everyone on the loan is 100% responsible for the entire debt.

Key Takeaway: While tenancy in common legally divides your ownership equity, it does not divide your mortgage liability. A default by one co-owner puts every single owner on the hook, potentially damaging everyone’s credit.

It’s a critical risk to understand before you sign on the dotted line with anyone.

Can We Switch From Tenants In Common To Joint Tenants?

Yes, you can change from tenants in common to joint tenants in Ontario, but it’s not as simple as just telling the Land Registry Office. The key here is that every single co-owner must agree to the change. One person can’t force it on the others.

The process requires a formal legal transaction. All owners must transfer the property from themselves (as tenants in common) back to themselves (as joint tenants) using a new Transfer/Deed of Land. This is done to establish the “four unities” of time, title, interest, and possession—the legal bedrock of a valid joint tenancy. You’ll need a real estate lawyer to draft and register the new deed correctly to ensure the change is legally binding.

What Happens If Tenants In Common Disagree On Selling The Property?

This is where co-ownership can get messy. You and your co-owner have a fundamental disagreement: one wants to sell, the other wants to hold on. Because tenants in common each have a separate share, but also the right to use the entire property, you can easily find yourselves at a stalemate.

If you can’t come to an agreement, Ontario law provides a way out. Any co-owner can apply to the court under the Partition Act to request an order for the “partition and sale” of the property.

Essentially, you’re asking a judge to break the deadlock. If the order is granted, the court can force the sale of the property, even over the objections of the other owners. Once sold, the money is split according to your ownership percentages on title. It’s the ultimate legal tool for resolving disputes when all other negotiations have failed.

Choosing between tenants in common and joint tenants is a decision with long-term consequences. At UL Lawyers, we help clients across Ontario navigate these complexities, ensuring their property ownership is perfectly aligned with their financial and personal goals. If you’re unsure about the wording on your deed or need help with estate planning, contact us for a consultation. We are based in Burlington but serve clients throughout the GTA and Ontario. Learn more at https://ullaw.ca.

Related Resources

Living Wills in Ontario: A Practical Guide for Modern Planning

Continue reading Living Wills in Ontario: A Practical Guide for Modern PlanningNEED A LAWYER?

We are here 24/7 to address your case. You can speak with a lawyer to request a consultation.

905-744-8888GET STARTED WITH A FREE CONSULTATION

Why Choose UL Lawyers

- Decades of combined experience

- Millions recovered for our clients

- No fee unless we win your case

- 24/7 client support

- Personalized legal strategies